- The Project

- Auto te Gast: How Infrastructures Shape Values and Behavior

- Elandsgracht: History and Context

- Other Fietsstraten

Elandsgracht: History and Context

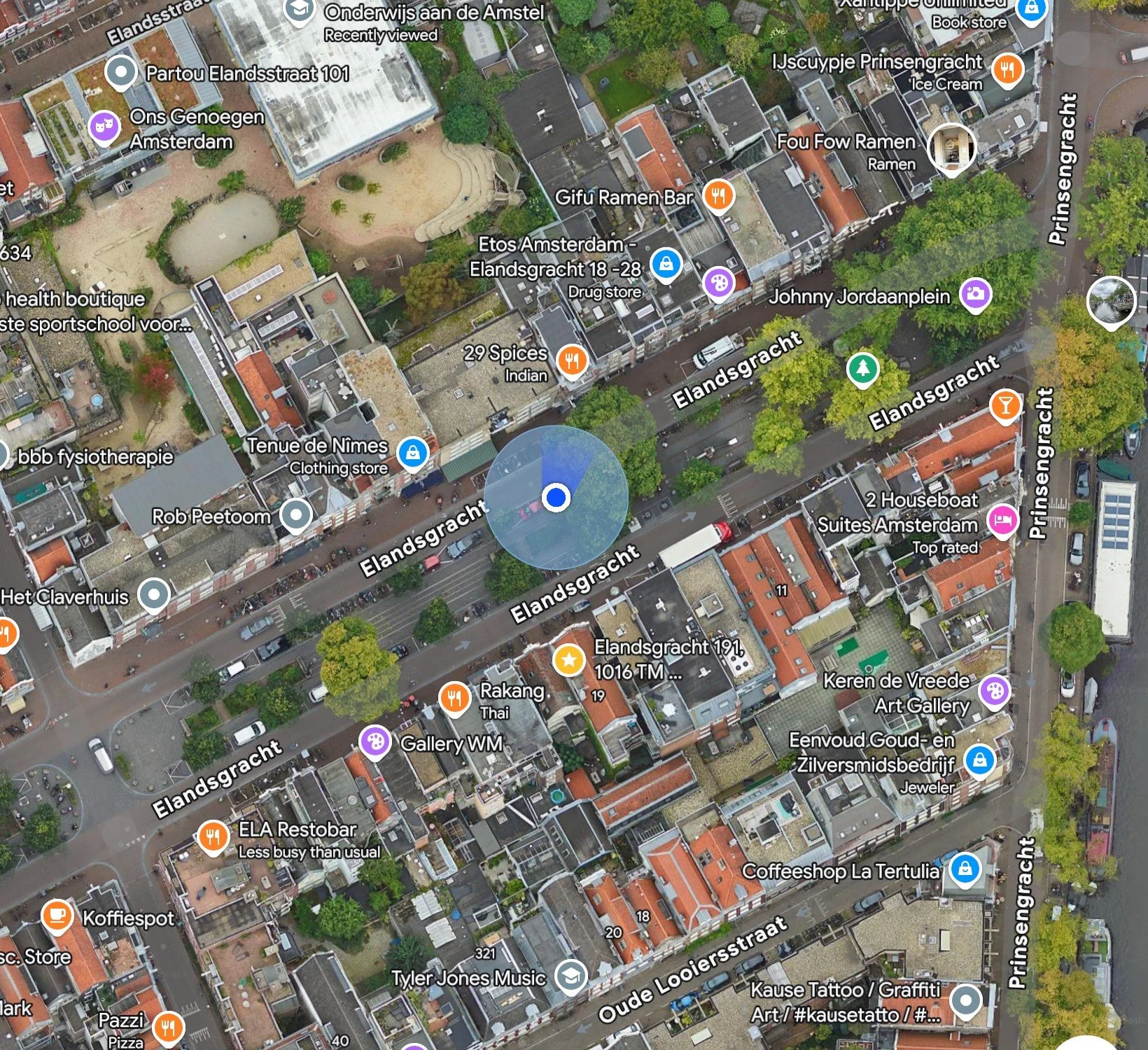

The film was shot entirely on Elandsgracht, viewed from a single fixed position over several days, edited to mirror the rhythm of one continuous day—from morning to evening. Once a canal where tanners processed hides, later filled to become a market street that sparked food riots in 1917, now a corridor marked by a strong sense of community that is threatened by gentrification, Elandsgracht embodies Amsterdam’s working-class and cultural history.

To linger here is to sense the street’s history and changing demographics: the disheveled folks drinking beer; the neighbors who pick up trash and water plants in the median; the cyclists intentionally slowing down big luxury cars. These overlapping uses—captured in long, static shots—reveal how public space accommodates multiple forms of life simultaneously.

The Elandsgracht canal was dug in 1612–1613, part of Amsterdam’s Derde Uitleg—the 17th-century expansion that created the Jordaan district for craftsmen, migrants, and small traders. Unlike nearby canals named after flowers, its name recalls the leather trade: eland (elk) hides were tanned here, filling the air with the smell of curing hides and producing the noxious effluent that giving Jordaan waterways their stench. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the canal was lined with narrow workers’ houses and small workshops, crowded with artisans and immigrant families.

As Amsterdam modernized, many Jordaan canals were filled in for sanitary and public health reasons. In 1891, Elandsgracht was covered over, creating a broad street that served as a hub for greengrocers and potato traders. This market economy shaped local life, but hardship was never far away. In 1917, food shortages sparked the “Potato Riot” at the market, when women and workers clashed with troops over access to food.

The street also carried the Jordaan’s cultural vibrancy. Folklore places the bandit Jacob “Sjako” Muller at nos. 71–77, remembered as a local Robin Hood. The early twentieth century brought neighborhood theaters, such as the Edison Theater, and later the music of Johnny Jordaan, whose statue stands on the corner with Prinsengracht.

By the postwar years, the Jordaan had fallen into decline, and sweeping demolition plans loomed. Activist and preservationist pushback in the 1970s shifted policy toward rehabilitation, sparing Elandsgracht from wholesale clearance. The street instead became home to new institutions, including the Amsterdam Police Headquarters and a bus station at Marnixstraat. More recent redesigns have added greenery, benches, and pedestrian space to the wide median.

In the early 2000s, Elandsgracht was redesigned with the visual and spatial language of the fietsstraat: dark red brick paving, a single narrow lane, calm traffic, and minimal markings. Only the section west of Lijnbaansgracht carries the official fietsstraat signage, but in practice the street’s design and rhythm continue seamlessly eastward across Marnixstraat.Today Elandsgracht is a broad, mixed-use street of cafés, shops, and community institutions such as the Claverhuis community center. Yet its layered past remains visible: gentrified yet still carrying the memory of working-class life and neighborhood solidarity.

It functions as a living example of shared urban space—where bicycles, cars, and pedestrians continually negotiate coexistence.